|

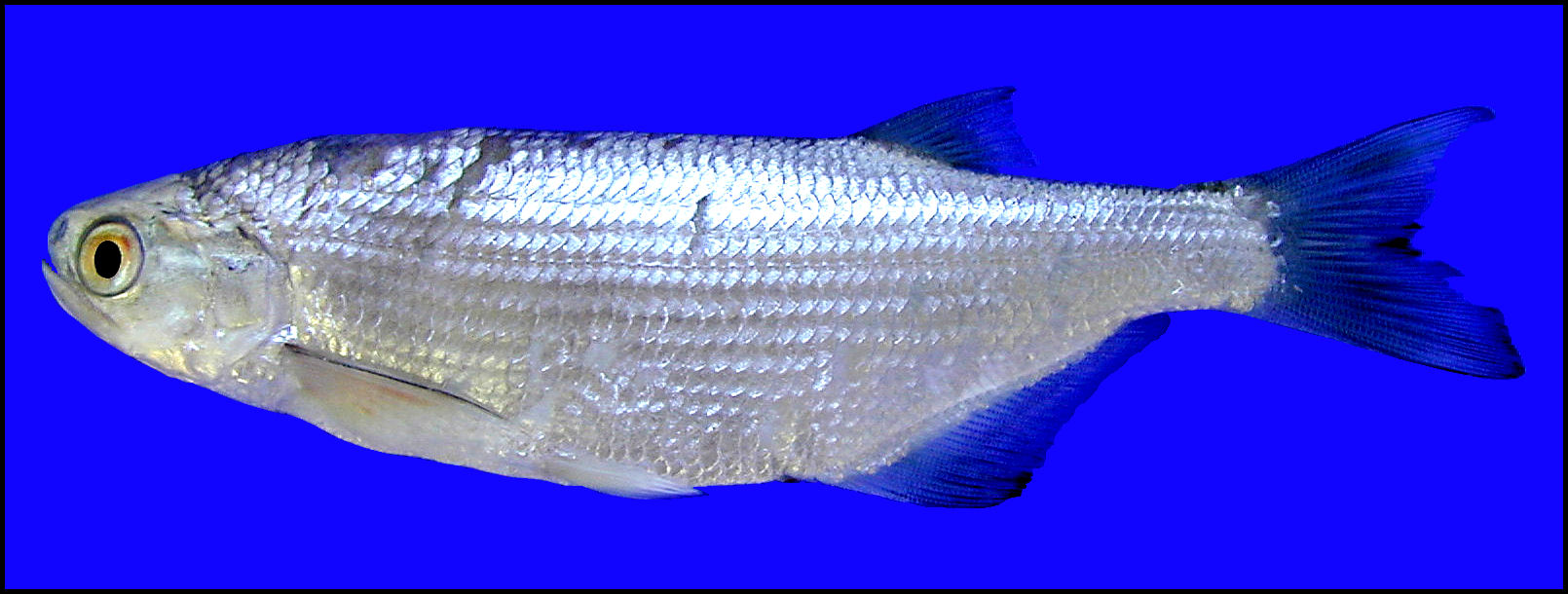

Picture by Chad Thomas, Texas State University-San Marcos |

||

|

Hiodon alosoides goldeye

Type Locality Ohio River (Rafinesque 1819), probably Falls of the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky (Gilbert 1980).

Etymology/Derivation of Scientific Name Hio - tongue or hyoid bone, don - tooth, refering to toothed tongue mooneyes (Hiodontiformes); alosoides - shadlike, referring to its resemblance to alosine shads (Scharpf 2005).

Synonymy Amphiodon alveoides Rafinesque 1819:421. Amphiodon alosoides

Characters Maximum size: 51 cm TL (Page and Burr 1991).

Coloration: Silver body; blue-green above with silver reflections, silver-white below; clear to dusky fins; gold iris (Page and Burr 1991).

Counts: Usually 9-10 dorsal rays, 29-34 anal rays, 57-62 lateral scales (Page and Burr 1991).

Mouth position: Superterminal (Goldstein and Simon 1999).

Body shape: Deep, compressed body; dorsal fin origin opposite or behind anal fin origin; large mouth; maxillary extends behind pupil of eye; blunt, round snout (Page and Burr 1991).

External morphology: Fleshy keel along belly extends from pectoral fin base to anal fin (Page and Burr 1991). Males can be separated from females, during the breeding season, by having anterior rays of the anal fin elongated forming a distinct lobe (Battle and Sprules 1960).

Internal morphology: Pyloric caeca present (Goldstein and Simon 1999).

Distribution (Native and Introduced) U.S. distribution: Ranges from the Northwest Territories, Canada, southward along the Mississippi basin to Louisiana (Hubbs et al. 2008).

Texas distribution: Restricted to the Red River basin (Warren et al. 2000; Hubbs et al. 2008).

Abundance/Conservation status (Federal, State, Non-governmental organizations) Special Concern (Hubbs et al. 2008); however, species is especially abundant in Lake Texoma. Currently Stable (Warren et al. 2000) in the southern United States. Common (Scharpf 2005); however, status is Endangered in Ohio and Wisconsin, Threatened in Pennsylvania, and Extirpated in Alabama. Gilbert (1980) noted that the species was common in some parts of range, but had disappeared from some areas (e.g. upper Tennessee River) where man-made changes, particularly impoundments, have modified natural conditions. Riggs and Bonn (1959) reported that abundance of this species in Lake Texoma (Oklahoma-Texas) had declined since 1956.

Habitat Associations Macrohabitat: Occupies a variety of habitats: medium to large rivers, small lakes, ponds and connected marshes, and muddy shallows of large lakes (Wallus et al. 1990). Species inhabits large rivers and lakes, and adjacent backwaters (Battle and Sprules 1960; Gilbert 1980).

Mesohabitat: Occurs in areas of moderate to fast current, as well as quiet pools; tolerant of highly turbid conditions (Gilbert 1980; Wallus et al. 1990). In Lake Texoma (Oklahoma-Texas), species abundant in open water in the clearer parts of the lake and in the tailwaters; usually taken near the surface; young-of-year are rare (Riggs and Bonn 1959). Lienesch et al. (2000) reported collection of seven specimens from cove section of Buncombe Creek (a tributary to Lake Texoma, Oklahoma-Texas). Collected from fast water around dikes and from the slower water around mud banks, in the Missouri River (Robinson 1977). Optimum temperature range 27-29°C (Becker 1983; Wallus et al. 1990).

Biology Spawning season: In Canada, May to July, at temperatures of 10-12.8°C (Battle and Sprules 1960; Gilbert 1980; Wallus et al. 1990). In the Missouri River, Missouri, two ripe females were collected in February when the water temperature was 0°C; on another occasion, young (less than 25.4 mm) were collected in May (Pflieger 1997). Species probably spawns in February or March in the Mississippi River at Keokuk, Iowa (Coker 1930).

Spawning habitat: Spawning occurs in pools of rivers or backwaters of lakes (Gilbert 1980). According to Wallus et al. (1990), species reported to ascend tributary streams and spawn; to spawn over gravel shoals; also in shallow inshore areas of lakes; and in pools in turbid rivers or in backwater lakes and ponds of rivers; spawning believed to occur in midwater; spawning associated with increasing or decreasing river flows.

Spawning behavior: Nonguarder; open substratum spawner; lithopelagophil – rock and gravel spawner with pelagic free embryos. Embryos have an adhesive chorion that soon become buoyant eggs; free embryos are pelagic by positive buoyancy or active movement, free embryos have limited embryonic structures, and larvae are unconfirmed nonphotophobic (Balon 1981; Simon 1999). It is thought that Hiodon alosoides spawns at night (Wallus et al. 1990).

Fecundity: Females sized 300-400 mm FL contained 5,800-25,200 (average 14,150) eggs; eggs are bathypelagic or semi-buoyant; eggs are spherical, 4 mm in diameter, having a wide perivitelline space, coarsely granular yolk, and a large oil droplet (Battle and Sprules 1960). In Montana, number of eggs per female varied from 4,288-10,164 (average 6,913; Hill 1966).

Age/size at maturation: Age at maturity tends to decrease from north to south with males maturing earlier than females (Wallus et al. 1990). Sexual maturity may occur at 114 mm TL (age 1); however most males are not mature until age 3 (265 mm TL) and females not until age 4 (298 mm TL; Miller and Nelson 1974; Wallus et al. 1990). In Montana, most ripe males were 3 years old and most ripe females were 4 years old; however, a few males were 4 and a few females 3 years old (Hill 1966). In Lake Claire, Alberta, Canada, males reproduce first at 6-9 years of age and females at 7-10 years, while in southern Manitoba, first maturity averages 2 to 3 years earlier than this (Battle and Sprules 1960).

Migration: Species apparently somewhat migratory during spawning season (Trautman 1981; Wallus et al. 1990).

Growth and Population structure: In Ohio, young or year specimens were 130-170 mm TL (Trautman 1981). Average calculated standard length at end of year of life for specimens from Lake Texoma (Oklahoma): 156 mm SL at end of year 1, and 183 mm, 232 mm, 260 mm, 274 mm, and 294 mm SL at the end of years 2-6, respectively; females were larger than males after the third year of life (Martin 1954). Average calculated total length at end of year of life for specimens from Red Lakes, Minnesota: 104 mm at end of year 1, and 211 mm, 287 mm, 328 mm, 358 mm, 381 mm, 401 mm, and 422 mm at the end of years 2-8, respectively (Grosslein and Smith 1959). Average calculated total lengths for Montana specimens in each year of life: 102 mm TL for year 1, and 203 mm, 259 mm, 290 mm, 307 mm, 328 mm, 394 mm, and 406 mm TL for years 2-8, respectively (Hill 1966).

Longevity: At least 14 years in some areas (Gilbert 1980).

Food habits: Goldstein and Simon (1999) listed first and second level trophic classifications as invertivore and drift, respectively; trophic mode – surface and water column; species often feeds at the surface; no indication of strong food influence, species will utilize whatever is most available; diet widely varied; bulk of diet of some fish comprised of aquatic and other insects. Gilbert (1980) listed food items: surface and aquatic insects, other invertebrates (including crustaceans and mollusks), occasionally small fishes. Hoopes (1960) reported that mayfly naiads (Hexagenia spp.) comprised 56% of the stomach contents of Hiodon alosoides collected from the Mississippi River (Iowa); Potamyia flava larvae made up about 19%; and immature Zygoptera and Odonata and fish formed the bulk of the remaining contents. Grosslein and Smith (1959) examined stomachs of specimens from Red Lakes, Minnesota and found that principal food organisms were aquatic insects (larval and adult); common occurrence of terrestrial insects suggested frequent surface feeding in shallow water; common occurrence of noctuid moths and fireflies in stomachs suggested that fish often fed at night. Specimens from the Mississippi River at Keokuk, Iowa fed almost exclusively on insects (listed in order of abundance: may-fly nymphs and imagos; beetles, mostly terrestrial but Gyrinus-whirlgig beetle and Stenelmis present also; caddisworms, midges, and beach flies; water boatman; dragonfly and damselfly larvae; grasshoppers and crickets; stone-fly nymphs; dobson-fly larvae or hellgrammites; Coker 1930).

Phylogeny and morphologically similar fishes Order Hiodontiformes (Nelson et al. 2004). Hiodon alosoides differs from herrings and shads in that it has a lateral line and an untoothed (fleshy) keel along the belly, while herrings and shads lack a lateral line and have a scaled keel (creating a saw-tooth edge) along the belly (Page and Burr 1991).

See Battle and Sprules (1960) and Wallus et al. (1990) for description of egg and larval development. See Hogue (1967) for additional information regarding identification of larval fish.

Host Records Crepidostomum illinoiense, C. opeongoensis, and C. cooperi have been reported from Hiodon alosoides (Choudhury and Nelson 2000). A pseudophyllidea cestode (Bothriocephalus), a papillose fluke (Crepidostomum illinoiense), and immature nematodes (family Camallanidae) reported from Lake Texoma (Oklahoma) specimens (Self 1954).

Commercial or Environmental Importance Commercially important in some places (Gilbert 1980).

References Balon, E.K. 1981. Additions and amendments to the classification of reproductive styles in fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes 6(3/4):377-389. Battle, H.I., and W.M. Sprules. 1960. A description of the semibuoyant eggs and early developmental stages of the goldeye, Hiodon alosoides (Rafinesque). J. Fish. Res. Bd. Can. 17(2):245-266. Becker, G.C. 1983. Fishes of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. 1052 pp. Choudhury, A., and P.A. Nelson. 2000. Redescription of Crepidostomum opeongoensis Caira, 1985 (Trematoda: Allocreadiidae) from fish hosts Hiodon alosoides and Hiodon tergisus (Osteichthys: Hiodontidae). J. Parasitol. 86(6):1305-1312. Coker, R.E. 1930. Studies of common fishes of the Mississippi River at Keokuk. Bull. U.S. Bur. Fish. 45:141-225. Gilbert, C.R. 1980. Hiodon alosoides (Rafinesque), Goldeye. pp. 74 in D. S. Lee et al., Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes. N. C. State Mus. Nat. Hist., Raleigh, i-r+854 pp. Goldstein, R.M., and T.P. Simon. 1999. Toward a united definition of guild structure for feeding ecology of North American freshwater fishes. pp. 123-202 in T.P. Simon, editor. Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Grosslein, M.D., and L.L. Smith, Jr. 1959. The goldeye, Amphiodon alosoides (Rafinesque), in the commercial fishery of the Red Lakes, Minnesota. Fish. Bull. (U.S.) 60(157):33-41. Hill, W.J. 1966. Observations on the life history and movement of the goldeye, Hiodon alosoides, in Montana. Proceedings of the Montana Academy of Science 26:45-53.

Hogue, J.J., Jr., R. Wallus, and L.K. Kay. 1967. Preliminary guide to the identification of larval fishes in the Tennessee River. Technical Note B19. Tennessee Valley Authority, Division of Forestry, Fisheries, and Wildlife Development, Norris. 66 pp.

Hoopes, D.T. 1960. Utilization of mayflies and caddis flies by some Mississippi River fishes. Trans. Amer. Fish. Soc. 89(1):32-34.

Hubbs, C., R.J. Edwards, and G.P. Garrett. 2008. An annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Texas, with keys to identification of species. Texas Journal of Science, Supplement, 2nd edition 43(4):1-87.

Kennedy, W.A., and W.M. Sprules. 1967. Goldeye in Canada. Fish. Res. Board Canada Bull. 161:45pp.

Lienesch, P.W., W.I. Lutterschmidt, and J.F. Schafer. 2000. Seasonal and long-term changes in the fish assemblage of a small stream isolated by a reservoir. Southwestern Naturalist 45(3):274-288.

Martin, M. 1954. Age and growth of the goldeye Hiodon alosoides (Rafinesque) of Lake Texoma, Oklahoma. Proc. Okla. Acad. Sci. 33:37-49.

Miller, G.L., and W.R. Nelson. 1974. Goldeye, Hiodon alosoides, in Lake Oahe: abundance, age, growth, maturity, food and the fishery, 1963-69, pp. 1-13. Tech. Pap., no. 79, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Nelson, J.S., E.J. Crossman, H. Espinoza-Perez, L.T. Findley, C.R. Gilbert, R.N. Lea, and J.D. Williams. 2004. Common and Scientific Names of Fishes from the United States, Canada, and Mexico. American Fisheries Society, Special Publication 29, Bethesda, Maryland.

Page, L.M., and B.M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. 432 pp.

Pflieger, W.L. 1997. The Fishes of Missouri. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City. 372 pp.

Rafinesque, C.S. 1819. Prodrome de 70 nouveaux genres d’animaux decouverts dans l’interieur des Etats-Unis d’Amerique, Durant l’anee 1818. J. Physique de Chimie et d’Histoire Naturelle 88:417-429.

Riggs, C.D., and E.W. Bonn. 1959. An annotated list of the fishes of Lake Texoma, Oklahoma and Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist 4(4):157-168.

Robinson, J.W. 1977. The utilization of dikes by certain fishes in the Missouri River. Federal Aid Project No. 2-199-R. Missouri Department of Conservation, Jefferson City. 14 pp.

Scharpf, C. 2005. Annotated checklist of North American freshwater fishes including subspecies and undescribed forms, Part 1: Petromyzontidae through Cyprinidae. American Currents, Special Publication 31(4):1-44.

Self, J.T. 1954. Parasites of the goldeye, Hiodon alosoides (Raf.), in Lake Texoma. The Journal of Parasitologists 40(4):386-389. Simon, T. P. 1999. Assessment of Balon’s reproductive guilds with application to Midwestern North American Freshwater Fishes, pp. 97-121. In: Simon, T.L. (ed.). Assessing the sustainability and biological integrity of water resources using fish communities. CRC Press. Boca Raton, Florida. 671 pp. Trautman, M.B. 1981. The Fishes of Ohio. Ohio State University Press. 782 pp.

Wallus, R., T.P. Simon, and B.L. Yeager. 1990. Reproductive Biology and Early Life History of Fishes in the Ohio River Drainage. Vol. 1. Acipenseridae through Esocidae. Tennessee Valley Authority, Chattanooga, Tennessee. 273 pp.

Warren, M.L., Jr., B.M. Burr, S.J. Walsh, H.L. Bart, Jr., R.C. Cashner, D.A. Etnier, B.J. Freeman, B.R. Kuhajda, R.L. Mayden, H.W. Robison, S.T. Ross, and W.C. Starnes. 2000. Diversity, Distribution, and Conservation status of the native freshwater fishes of the southern United States. Fisheries 25(10):7-29.

|

||

|

|

||